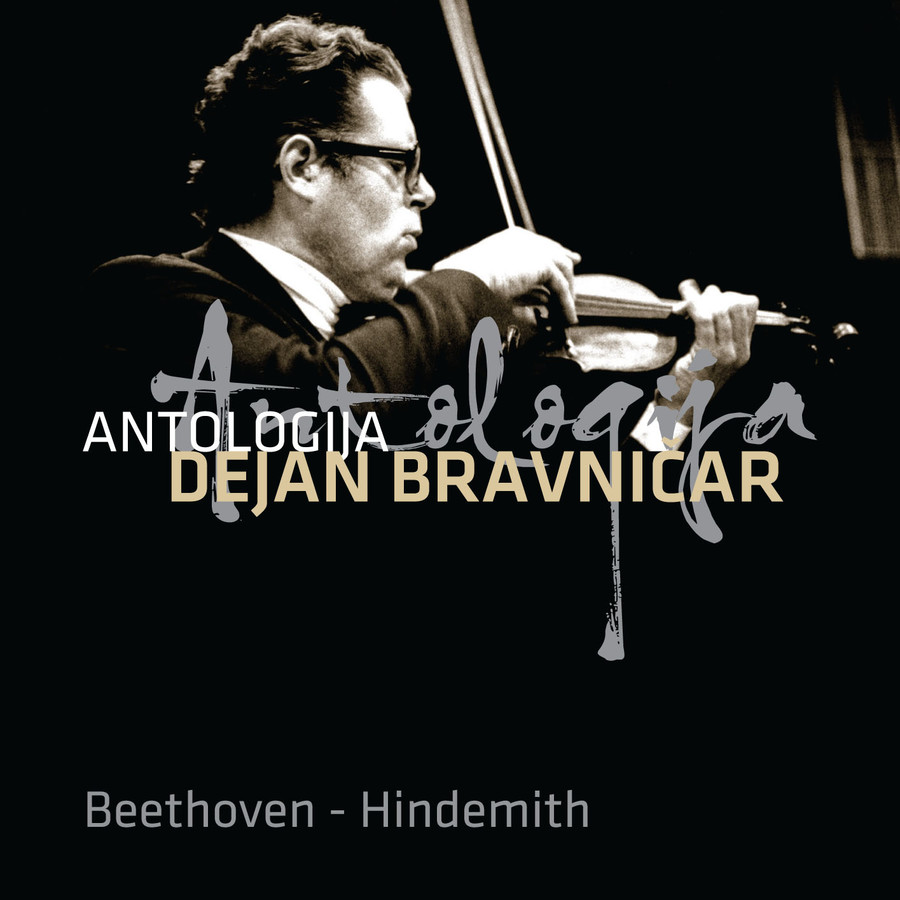

DEJAN BRAVNIČAR

ANTOLOGIJA - DEJAN BRAVNIČAR: MOZART, BRAHMS

Classical and Modern Music

Format: CD

Code: 114724

EAN: 3838898114724

The time of the creation of the series of five violin concertos by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756 – 1791) has been and remains the subject of numerous debates. It is generally agreed that they were not written in a short period of time, as was initially assumed, but we can certainly place them in the period between 1771 and 1775. Similarly, little is known about whom they were actually written for. Mozart may well have composed the concertos for

himself to perform, as he was not only a top pianist of his time, but also a good violinist. In fact, the Archbishop of Salzburg engaged Mozart both as a composer and a concertmaster. In any case, he knew the instrument well, as he had received excellent instruction. His father and first teacher, Leopold Mozart, was an important violinist and in the year of Wolfgang’s birth published a book entitled Versuch einer gründlicher Violinschule, which became one of the fundamental works of violin

pedagogy of the eighteenth century. It was translated into several languages and regularly reprinted right up until the middle of the nineteenth century. In addition to his father’s influence, the young Wolfgang also met most of the best virtuosi of his time in Italy, including Giuseppe Tartini, Pietro Locatelli, Pietro Nardini and others.

In terms of compositional design, the young composer made remarkable progress in the course of his violin concertos. The first two concertos, which are rarely performed today, still belong to the Baroque and Rococo tradition, which obviously did not satisfy Mozart. In the last three concertos, his mastery grew both in terms of form and content, and in many ways Violin Concerto No. 5 in A major already approaches the concerto form of the nineteenth

century.

This concerto stands out in several respects. The tempo marking of the first movement, Allegro aperto, is itself unusual, seldom appearing even in Mozart’s works. Compared to the usual Allegro, it signifies a slightly calmer tempo with a more sublime character. After a typically Mozartian introductory theme, the solo violin enters in the tempo Adagio, an approach that is unique in the composer’s entire opus of instrumental concertos. Only then does the Allegro

follow. The second movement, Adagio, is the most extensive and profound slow movement of the master’s violin concertos. Interestingly, Mozart actually wrote a substitute slow movement, also in E major (KV 261), which is today performed as an independent composition, and not as a concerto movement. The next surprise appears in the final movement, which is in rondo form. The usual rapid first theme is replaced by a calm minuet, while the central section is conceived as an Allegro in two-four

time, in the style of the then fashionable “Turkish” music, which is reflected both in the rhythm and the chromatic melodies, as well as in the special rhythmic colouristic effect of the contrabasses and cellos playing col legno. The combination of different metres, tempi and musical styles creates a contrasting whole that is a perfect substitute for the usual fast movement.

In all respects, Violin Concerto No. 5 in A major, KV 219 represents the pinnacle of the composer’s creativity in this genre, and remains among the most frequently performed violin concertos today.

From 1877 to 1879, Johannes Brahms spent the summers in the idyllic village of Pörtschach am Wörthersee in Carinthia. During the first summer there, he composed the Second Symphony in D major, Op. 73, while the following summer saw, among other works, the completion of the first draft of the Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 77. At the end of the summer holidays, he sent the solo part of the concerto to his friend, Hungarian violinist, conductor and

composer Joseph Joachim, to whom the work is dedicated. Brahms asked Joachim to express his opinion frankly and, without any hesitation, to correct or mark particularly difficult, awkward or unperformable passages. Joachim, who found “... a great deal of genuinely good violin music” in the solo part, actively contributed to its final shape. Brahms originally conceived the work in four movements, but, for a variety of reasons, later opted for the usual three movements, replacing the Adagio and

Scherzo with a “weak” Adagio, as he himself said.

The concerto was premiered by Joachim as soloist and Brahms as conductor at the Gewandhaus in Leipzig on New Year’s Day of 1879. Joachim played his own cadenza, which is still the most commonly performed cadenza today. There followed performances in other music centres. The work was generally well accepted by the audience, while the critical response was rather mixed. Some conductors remarked that the concerto was not a work “for the violin”, but “against the violin”. Violinist Henryk

Wieniawski described the concerto as unperformable, while a resentful Pablo Sarasate declined to perform the work, stating that he would “not stand on the podium with a violin in his hand and listen to the oboe playing the only melody in the slow movement”.

Such responses by Brahms’s contemporaries are, to some extent, understandable. Contrary to the tradition, Brahms did not intend to write works for a display of virtuosity, but rather, following Beethoven’s example, held to higher musical goals. The fact that the concerto is a symphonically conceived composition with a solo violin part is not only suggested by the original four-movement scheme, but also by the dimensions of the individual movements. The first

movement, Allegro non troppo, is in classical sonata form, with the violin entering only in the ninetieth bar. The second movement, Adagio, has a typical tripartite form, while the third movement, Allegro giocoso, ma non troppo vivace – Poco piu presto, is in rondo form with a principal “Hungarian theme” that can be understood as a tribute to Joachim. Despite being in the “violin-friendly” key of D major, Brahms’s Violin Concerto is extremely demanding technically. Many performers and experts

initially attributed the level of difficulty to the fact that Brahms was a pianist and not a violinist, but today the general opinion is that the concerto’s solo violin part is difficult because the composer conceived it primarily in the service of musical content.

Dr. Borut Smrekar

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791):

Violin Concerto No. 5 in A major, KV 219 *

1 I Allegro aperto 9:57

2 II Adagio 10:35 (listen!)

3 III Rondeau: Tempo di menuetto 9:19

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897):

Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 77 ⁰

4 I Allegro non troppo 22:50

5 II Adagio 9:31

6 III Allegro giocoso, ma non troppo vivace 8:02

Dejan Bravničar, violin

RTV Ljubljana Symphony Orchestra

Samo Hubad, conductor *

Anton Nanut, conductor ⁰

Recorded: Slovenska filharmonija, 1976 (1-3), 1984 (4-6).